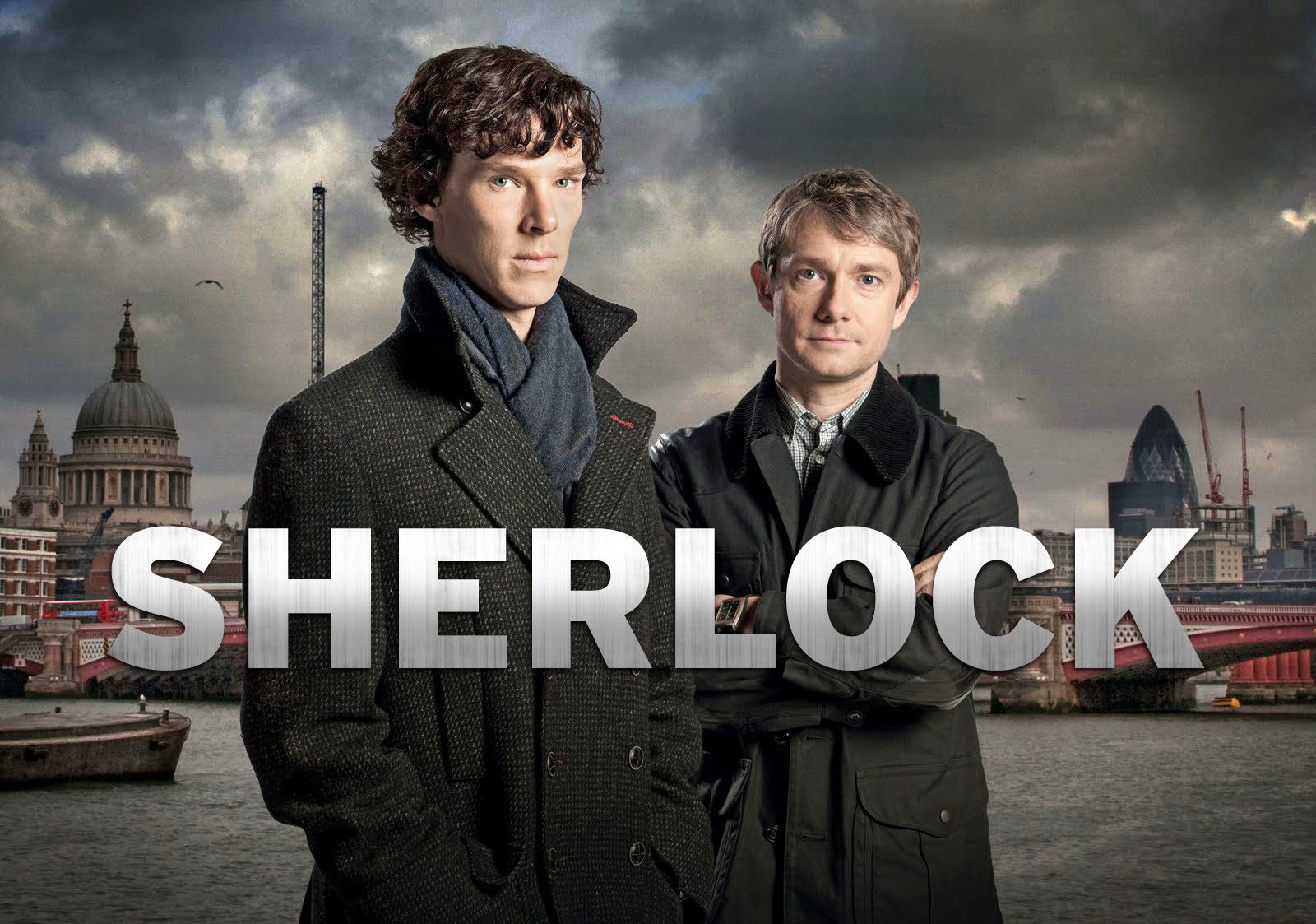

The problem with reviewing Sherlock (BBC1) is that all you really want to do is quote from it. Sherlock on his new relationship, perhaps: “We’re in a good place. It’s very affirming.” Watson: “You got that from a book.” “Everyone got that from a book.” Or maybe Watson leaning towards the bodyguard who takes a tyre iron the good doctor had been carrying in his pocket and murmuring: “It doesn’t mean I’m not pleased to see you.” Or Sherlock to Mycroft: “Don’t appal me while I’m high.” Or – but you get my drift.

His Final Vow was the third and final part – already! I know! – of the new series of Sherlock. There have been vociferous complaints about the previous two episodes, their main collective thrusts being that the first once had pandered too much to the fans but failed to deliver a truly satisfactory explanation of Sherlock’s survival of his Reichenbach fall, the second had been too self-indulgent and crime-free in its focus on Watson’s wedding.

To my mind, the first episode dealt triumphantly with the whole problem – or exploited to the full the opportunity, depending on your mindset – offered by the viewers’ deep and joyous engagement with the series. It met some expectations, toyed with others and went “Yah, boo, sucks!” to the rest with the same kind of authoritative playfulness that all along has helped make us love it so. Yes, the second episode might conceivably have benefited from a few minor nips and tucks along the way. But I am willing to overlook these infinitesimally small flaws in return for the ceaseless flow of wit, invention and intelligence being delivered to me via a set of performances (and here I feel we must prostrate ourselves at the feet of Una Stubbs’ Mrs Hudson, who has been the candied cherry on the hand-piped icing on the world’s most delicious cake this series) so finely calibrated, by turn so careful, so showy, so heartbreaking, so hilarious, and always so attuned to each other that together their story is even greater than the sum of its astonishing parts. Yes. I consider that the bargain of the bloody year.

As for last night’s episode, a reworking of Conan Doyle’s The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton for a privacy-obsessed digital age – I can’t be sure, but I think it was perfect. I’ve been sitting here a long time trying to imagine what anyone could find to object to in it and I can’t think of anything. Of course I recognise that this will probably prove to be a failure of critical faculty or, less professionally devastatingly, simply imagination, but I think congenital nitpickers and naysayers must have had a bad night. Maybe Lars Mikkelsen was too perfectly pitched as Charles Magnussen, the “king of the blackmailers” reimagined as a foreign-accented, rimless-spectacled newspaper magnate at the centre of an inquiry into whether he holds too much influence over those who should be seeking to constrain instead of appease him. Maybe there were too many unseen twists that flicked you off your feet because you were already bubbling with delight and dizzy from the smart, witty, fleet exchanges whipping back and forth? Did you land too hard on your bum?

Advertisement

Or maybe, like the German emperor convinced that Mozart’s music has too many notes, it was simply all too much? This final part of the triptych not only had all the attributes that make every episode of Sherlock great, but made further sense of the previous two from this series and set fair the next one to be something of a humdinger too. It makes the rest of telly look like a clunking mass of decrepit, ill-fitting parts. It’s solved the problem of how to integrate and represent new technologies onscreen. It repeatedly solves the problem of how to update, expand and reinvigorate something without losing its spirit. And it has solved the problem of how to invest modern fictional characters with modern real people’s knowingness, our constant self-awareness, the all-pervasive irony that is now indivisible from ourselves and how we live. “I’ve thought long and hard about what to say to you. These are prepared words, Mary,” says Watson, because creators Steven Moffat’s and Mark Gatiss’s genius lies in realising that we no longer live in a way or in a world in which we can even pretend that they could, in his situation, be any other way.