With the holiday movie season just around the corner, the television screen is loaded with star-studded clips that help you decide your Friday night date plans in 60 seconds or less. The right trailer can make or break a movie’s starting weekend. But how did these sometimes epic teasers get their start? Let’s explore the origins of the cinematic ritual that can swing a picture to blockbuster or bust.

What used to be shown at the end of a feature film, thus the term “trailer”, is now seen on home television, in theaters and is the #3 form of video viewed online today. In 1912 at Rye Beach, NY, a concession stand hung a sheet to show a film clip for the upcoming installment of The Adventures of Kathlyn. Viewers could only find out if Kathlyn escaped the lion’s den by coming to see next week’s exciting chapter. From there, it was the Loew’s theater chain that showed the first of what was to become a staple of movie making. In 1913, Nils Granlund, adman for Loew’s, pulled together a promotional film of The Pleasure Seekers, a soon-to-be-opening musical on Broadway. In order to capitalize on the captive audience, film of the rehearsals and other key production facets were shown to theater goers to induce them to head to Broadway.

Granlund took the concept further the next year by using a slide approach to promote an upcoming Charlie Chaplin movie at the Loew’s Harlem location. With a new way to provide announcements and information, Granlund’s technique was quickly becoming adopted by theater management across the country willing to pay for the latest technology. Paramount Studios grabbed hold of this practice and in 1916 began to release trailers for its high-profile films. In 1919 they added a trailer division to the studio to promote all their upcoming films.

Studios recognized this burgeoning business but were slow to climb aboard. Trailer companies began to sprout in the New York region featuring attractive slides since they were unable to get their hands on the actual film footage. As studios were beginning to purchase theater venues, they became more interested in how their films were being marketed. A trio of New Yorkers saw the opportunity and formed the National Screen Service (NSS), a company to handle the promotional issues and distribution efforts for the studios in exchange for exclusive access to the films.

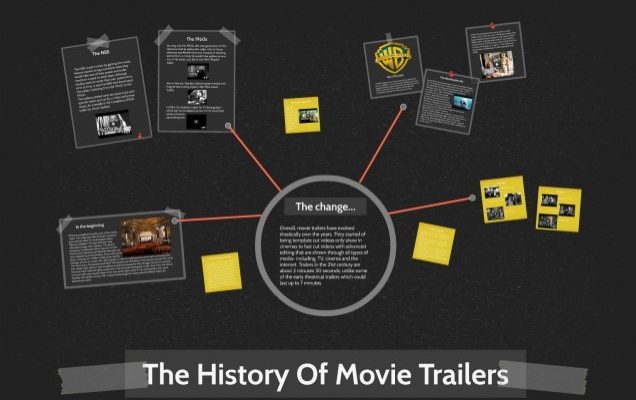

The NSS was the primary trailer firm from 1927 to the 1970s using the studio’s editing rooms, equipment and idle editors to produce a standard movie product for much of that time. The look and sound was similar in nature: loud, sensationalistic, title-strong glimpses of the story on film. It wasn’t until Gone With the Wind that a more even toned, lighter trailer emerged. Along the same time, Cecil B. DeMille developed the hammy, more outrageous versions with heavy voice-overs and startling pictures to captivate the viewers while Alfred Hitchcock developed his own quirky, humorous brand of promotion. His trailer for Psycho featured a tongue-in-cheek “Hitch” touring the Bates Motel and Mother’s mansion. He also used the new concept of “special shoots” or individually shot scenes used just for the trailer. It was freeze frame capability that led to the discovery within the Psycho trailer that the person in the shower was actually Vera Miles in a blonde wig stepping in for Janet Leigh who was unavailable.

As the production quality became more important and studios began searching for more individualized methods of advertising, stars took to narrating certain films and the trailers became more character oriented. Trailers began focusing on the plot and personas rather than the A-list actors involved. As movie goers’ tastes evolved, film makers evolved by branching out to location shooting and more effects. This meant a more sophisticated trailer which gave rise to more outside firms with fresher techniques and innovative ideas.

Studios were searching for new graphics, narrations and music to change up the staid, cookie-cutter productions which had come from NSS for so many years. In the 1960s the direction moved toward even more modernization and artistry with boutique firms which specialized in certain film genres. With the increasing advances and popularity in television, studios began to take notice of the small screen ads for their style and also their usefulness in promoting their films.

As the ’60s wore on, the NSS began to be relegated to only time-definite film distribution since studios could produce their own, lower-cost promotional products without them. As trailers evolved, so did the methods of using them. With a new decade came new ways to innovate the making and marketing of movies and their trailers. Clips deemed as the best were used as well as special shoots and even deleted scenes. Studios began buying out whole venues for new showings enabling them to capture all profits from the screenings. With the 1975 release of Jaws, a new platform debuted as well – – the nationwide, same-day release.

With the advent of the MTV generation also came a new generation of movie promotion. Music videos and movie trailers share certain similarities such as time constraints. With compelling music, editing techniques and narrative expertise, producers can make the most of any movie in the two and one half minutes allotted. The modern-day trailer’s first act, main body and denouement can succinctly summarize a plot, making any film the “best new hit of the year”. And since the choice of trailer music can be anything from other movie scores, classics, popular music or a standard from the library, the audience can be moved to tears, joy or fear before the soundtrack has ever been written.

As technology presses on, the industry will eventually see digital trailers replace the celluloid standards just as digital film copies will replace celluloid films. Targeting will become more specific; an internet trailer geared toward a specific genre audience will be constructed differently than its cousin, the theater trailer, giving studios more control of trailer placement while at the same time giving them the most flexibility yet.

From a sheet in Rye, NY to digital releases of epic movie promotional pieces, the trailer has evolved into a communication device, an art form, a method of persuasion and a lucrative industry. As Cameron Diaz said in The Holiday, “That’s why they pay me the big bucks”.